|

Fifteen Frequently Asked Questions

- Q1: Hasn't Egyptian chronology, which CoD challenges, been firmly fixed by 'Sothic'

astronomical dating? [Answer below]

- Q2: Can Radiocarbon Dating prove CoD right or wrong? [Answer below]

- Q3: Do the results from the developing dendrochronology for Anatolia agree or

disagree with CoD? [Answer below]

- Q4: Where does CoD stand with the scientific dating for the explosion of Thera which

is raising, rather than lowering, Bronze Age chronology? [Answer below]

- Q5: Has Professor Kenneth Kitchen shown that the CoD restructuring of Egyptian

chronology is impossible? [Answer below]

- Q6: Egyptologists say that they can retrocalculate, by means of 'dead reckoning', from

securely dated later dynasties back through the Third Intermediate Period to the New

Kingdom. Is this true? [Answer below]

- Q7: But how can you dispute the obvious similarity between the names Shoshenq and

Shishak? [Answer below]

- Q8: Is it true that the conventional chronology of Egypt is supported and proved to be

correct by its synchronisms with the chronology of Mesopotamia? [Answer below]

- Q9: How valid is the statement that CoD makes nonsense of Biblical history by placing

King David in the middle of the reign of Ramesses II? [Answer below]

- Q10: If the Philistines arrived in Canaan in the time of Ramesses III, whom CoD makes a contemporary

of King Solomon, how could they have fought his predecessors Saul and David as mentioned in

the Old Testament? [Answer below]

- Q11: Have any valid criticisms been levelled at CoD which

the authors have not been able to answer? [Answer below]

- Q12: Is there any truth in the rumour that scholars have

fabricated or falsified evidence in order to disprove CoD?

[Answer below]

- Q13: Have any of the conclusions in CoD been accepted by

other archaeologists and ancient historians? [Answer below]

- Q14: Why has CoD not been generally accepted as the

correct chronology for the ancient world? [Answer below]

- Q15: Is there a single test that can be done to prove or

disprove CoD? [Answer below]

References here

Q1: Hasn't Egyptian chronology, which CoD challenges, been

firmly fixed by 'Sothic' astronomical dating?

No it has not. The Sothic theory depends on a number of

assumptions which do not stand up to close scrutiny.

Since our first published criticisms (James et al. 1987,

71-74) there has been a sea-change in opinion as to the

reliability of this astronomical dating.

Two key references to the rising of the star Sirius

(Sothis) provide the lynchpins for the conventional

chronology of the Egyptian Middle and New Kingdoms

respectively. Both of them have been effectively

scotched. Senior Egyptologist W. Helck (1989, 40-41)

pointed out that the Ebers Papyrus, which supposedly

provides the Sothic fixed point (traditionally 1517 BC)

for the New Kingdom, does not actually contain a calendar

date - so that it is useless for any calculations. The

Middle Kingdom fixed point (traditionally 1872 BC) derived

from the Illahun Papyri now faces serious problems raised

by L. Rose (1994), who has demonstrated that the lunar

data mentioned in the same documents cannot fit a date in

the 19th century BC.

As there are no longer any reliable astronomical fixes,

Egyptologists have, by and large, abandoned their reliance

on Sothic dating - although they have been rather slow in

admitting it in public.

Q2: Can Radiocarbon Dating prove CoD right or wrong?

Although this method has the potential to do so, C14

results from the relevant areas are at present generally

unsatisfactory. For prehistoric cultures earlier than, or

unrelated to, the Egyptian dynasties, archaeologists

regularly test dozens of samples. By contrast, for the

Late Bronze and Iron Ages, they have tended to assume

that, as the chronology is 'known', radiocarbon tests are

not really needed. As well as the shortage of results,

inappropriate samples have usually been chosen, mostly of

wood and charcoal which, unless selected with extreme

care, will give dates much older than the context they

come from. There have also been many problems at

laboratory level, such as varying degrees of pretreatment

to remove contamination. Calibration raises further

difficulties, as the statistical variables involved are

often poorly understood. Consequently most C14 dates for

the period in question amount to little more than 'window

dressing' for a site report.

From another perspective, it is also well known that

numerous radiocarbon dates from sites in the Aegean, Egypt

and the Near East, have never been published because they

do not suit preconceptions - a phenomenon we have dubbed

the 'publishing filter'. Though it is rarely admitted in

print, there are documented cases from at least three

sites (see James et al. 1998, 36).

Given all this, we strongly feel that the radiocarbon

dates currently available are not adequate to judge the

CoD theory. New series of tests need to be performed on

good materials from secure contexts, with the samples

divided between at least three laboratories for cross-checking as results can differ between them. In one case

in the 1970s the same Egyptian samples were tested by the

Pennsylvania, British Museum and Uppsala labs (Olsson &

El-Daousay 1979). The dates from the first two generally

fitted the conventional chronology but those from Uppsala

were consistently lower and fit well with our chronology.

Had Uppsala alone done the tests it would have looked as

if radiocarbon had proved CoD correct! The Uppsala

laboratory took pride in its careful pretreatment of

samples to remove contaminants, a fact which may perhaps

explain the divergent results. We would not, however, use

these old tests to reinforce our case. There is

increasing realisation, due to enormous improvements in

the method, that all determinations from before the 1990s

should really be discarded.

So until new series of good quality dates are produced

we simply cannot say whether radiocarbon can prove CoD

right or wrong. The C14 database from Greece is, like

that from Egypt, a shambles, and we would fully agree with

the following statement made by Sturt Manning (1990, 37)

of Reading University:

... new series of highly quality dates from sealed

stratigraphic contexts from all the Aegean periods are

required. The current corpus consists of dates from

very different technical processes, and dates usually

lacking carbon-13 normalization, or alkali pre-treatment! This is unacceptable... The pressing need

is therefore for Aegean radiocarbon dates with the

contextual and measurement quality to match the

precision of the current radiocarbon calibration

curves.

Yet only two years later, with no new C14 dates (but

not without a degree of hypocrisy), Manning and his

colleague Weninger (1992) attempted to use the available

results from the Aegean to show that CoD was wrong! Their

article, published in Antiquity, has been repeatedly

cited. This is unfortunate, as it contained a number of

serious methodological errors. Most of the C14 results

they used, some going back to the 1950s (!), came from

unsuitable samples of wood and charcoal. We have

published a detailed response (James et al. 1998, 36-38)

showing that if due attention is paid to the context of

the samples, the presently available radiocarbon dates for

the end of the Late Bronze Age in Greece fit comfortably

with our model.

Q3: Do the results from the developing dendrochronology

for Anatolia agree or disagree with CoD?

As with radiocarbon, some loose claims have been made

about tree-ring chronology conflicting with the CoD

model, but a balanced assessment reveals a very different

picture.

Professor Peter Kuniholm and his Cornell University

team have established a 1503-year 'floating sequence' of

tree-rings for Bronze and Iron Age Anatolia. When this

has been extended to the point where it becomes continuous

with modern sequences, it should provide the best

yardstick for testing CoD - circumventing some of the

uncertainties involved in C14 dating. At present,

however, Kuniholm's 'floating' sequence is still reliant

on radiocarbon for its absolute dates. In the words of

Professor Lord Colin Renfrew (1996, 734):

Their work offers the best hope we have for a really

sound chronology for the later prehistory and history

of the Near East and Egypt, and indeed the eastern

Mediterranean in general. But their work is not yet

complete.

On the release of CoD, Kuniholm unfortunately began

giving misleading impressions of what his dendrochronology

could show with respect to the c. 250 years we wished to

eliminate: "I have tree-ring sequences, which cover almost

all those nasty centuries, and they're there." (Reported

in Brown 1991, 15). This completely missed the point. We

are not disputing that trees grew during the 12th, 11th

and 10th centuries BC! The question is whether those

tree-ring centuries are linked with post-Hittite cultures

(as the conventional chronology would have it) or with

those of the Hittite Empire (as our model predicts). If

Hittite buildings destroyed at the very end of the Late

Bronze Age were to be found exclusively with timbers

dating from considerably before 1200 BC, then our theory

would be in trouble.

The blue door-post from Dispilio.

© N. Kokkinos, 1999

|

We stress the word exclusively here, because as with

radiocarbon dating there is an 'old wood' problem in tree-ring dating. Dendrochronology can rarely give us a date

when a particular piece of wood was used; even less often

will it give a date for an archaeological destruction.

Dendrochronology gives us the dates when tree rings grew,

so one has to be very careful about using it to date

archaeological levels. Kuniholm himself has noted many

examples of centuries' old tree-rings incorporated into

much later structures and he frequently recommends

caution. A recent and extraordinary case concerns a piece

of wood he collected at Dispilio-Kastoria in northern

Greece, near a Neolithic lakeside settlement:

A well-preserved juniper post, painted blue and with

modern door hinges, was recovered from a modern village

house simply because it looked suspiciously old. The

sample we were given did not fit anything in our

Neolithic inventory, so we sent a piece of it to

Heidelberg to see what radiocarbon analysis would

reveal. The date is 2117 B.C. + 110 years, which means

it is from some Early Bronze Age occupation near the

lake at Kastoria. (Kuniholm 1998, 4)

Yes, this does actually mean (given the right climate and

conditions) that four thousand-year-old pieces of wood can

be reused in building! Given the 'blue door' phenomenon,

it should be obvious that the latest dendro dates from a

structure, site or culture are the most significant.

There is now dated tree-ring material from a handful of

sites of the Hittite period. Unfortunately the most

poorly published of these results has received the most

attention from our critics. This is from Masat Hüyük,

where preliminary reports gave a dendro date of 1392 + 37

BC (since then lowered to 1353 + 1 BC) for a site

associated with the 14th-century Hittite king

Suppiluliuma. As Suppiluliuma is generally thought to

have died c. 1320 BC, the result represented, in the view

of Professor Anthony Snodgrass (1991), "a shot in the arm"

for the conventional chronology. The problem is that the

information given about the context of this wood sample

makes no sense in terms of the stratigraphy as it was

published by the Turkish excavator - and may indeed turn

out to be a "shot in the foot". There are three levels

from the site, and Kuniholm's comments have muddled them

together (James et al. 1998, 38). More worrying, in a

private letter to us, he revealed that a sample from an

earlier level remains unpublished; as far as he could

remember, it postdated the published result. This would

completely invalidate the significance of this dendro-date. Despite numerous appeals since 1991, Kuniholm has

yet to retrieve and publish the full data from the site.

Only the results from one Hittite site have been

formally published, those from Tille Höyük on the

Euphrates. These were striking. The construction of the

last phase of the Tille Höyük Gateway is dated to 1101 + 1

BC, with its use lying in the 11th century BC. Yet Tille

Höyük was an Imperial Hittite outpost, which on the

conventional chronology would have been constructed about

1300 BC, and destroyed c. 1190 BC. The dendro-date is

clearly impossible for the conventional chronology.

Furthermore, the best fit for this sample (using the

normal T-score statistical test) is actually in 942 + 1 BC

(James et al. 1998, 41, n. 10)! An extra statistical test

had to be introduced to avoid this awkward conclusion.

Kuniholm does indeed have tree-rings for those "nasty

centuries". Nastily for the conventional chronology, at

Tille Höyük they are associated with the remains of an

Empire which was supposed to have fallen at least a century

earlier.

Q4: Where does CoD stand with the scientific dating for

the explosion of Thera which is raising, rather than

lowering, Bronze Age chronology?

In the mid-1980s dendrochronologists proposed a way of

dating the explosion of Thera scientifically. They

suggested that narrow tree-rings (caused by frost) around

1628 BC in North America reflected the adverse weather

caused by the volcano. Such an event seemed to be

confirmed by later finds of frost-ring damage in Irish

tree-rings and a peak of sulphuric acid in the Greenland

ice-cores. This ran counter to the archaeological dating

of the Thera explosion to c. 1500 BC.

Both vulcanologists (notably David Pyle of Cambridge)

and archaeologists (notably Peter Warren of Bristol)

advised caution about such "proxy dating". Frost-ring

damage and acidity peaks might well be caused by volcanic

eruption, but there was no evidence to show which volcano

was responsible. Nevertheless, by the 1990s an increasing

number of scholars had jumped on the 'scientific dating'

bandwaggon, attempting to raise the beginning of the Late

Bronze Age Greece to accommodate the 1628 BC date.

Manning (1992), for example, insisted that the 1620s acid

peak was the only signature in the ice-cores which was

close enough in time to match the Thera event.

We have always remained sceptical of the case for a

high date for Thera, suspecting that the whole thing would

eventually fall through. Unfortunately, our position

recently led an otherwise favourable reviewer to remark

that we took a "sceptical view of the new scientific

dating techniques" (Gerding 1997/8, 160), which is far

from the truth. Proxy dating is not to be confused with

the scientific techniques themselves.

As it happens, we have now been vindicated. When

further work was published on the Greenland ice-cores the

real reason why the 1620s date looked so conspicuous

became clear. Due to budgetary constraints, a thorough

search measuring the sulphuric acid from each year had

never been undertaken! When this was done, the 1620s BC

'event' ceased to be special. Similar peaks of sulphuric

acid are now known to exist in the 16th, 15th, 14th and

13th centuries (Zielinski et al. 1994)! Any of these (for

example those from the ice-core years 1594, 1454, 1327 and

1284) might represent the Thera eruption. Worse still,

small particles of volcanic ejecta have now been found in

one of the very ice-levels from Greenland. Analysis has

shown that their chemical composition does not match that

of Thera (Zielinski & Germani 1998a). Clearly miffed,

Manning (1998) published a "correction" to the geologists'

conclusions, arguing that they had misinterpreted their

data and that the particles came from Thera after all.

The geologists' response (Zielinksi & Germani 1998b)

stated, in as many words, that Manning was out of his

depth and simply did not understand the methods involved.

Apart from the entertainment value of watching these

developments from the sidelines, we are now able to stress

that there is no longer any 'scientific' consensus on the

high dating. Indeed, the direct evidence from the

Greenland ice-cores suggests that the c. 1628 BC event

should not be linked with the explosion of Thera, but with

that of an unidentified volcano.

In short there is no good evidence for raising the

dates for the beginning of the Late Bronze Age in Greece,

rather than lowering them - as we feel should be the case.

(Even though, strictly speaking, a raising of the

beginning and a lowering of the end are not mutually

exclusive, as the real length of the Late Bronze Age

remains sub judice.)

Q5: Has Professor Kenneth Kitchen shown that the CoD

restructuring of Egyptian chronology is impossible?

Far from it. In his review of CoD in the Times Literary

Supplement, Kitchen (1991a) claimed that our proposed

overlaps between the dynasties of the Third Intermediate

Period are "ruled out by a mass of evidence. A single

example must suffice."

For his example he chose the 21st Dynasty, claiming

that the successor of Siamun, penultimate ruler of this

dynasty, was the brother-in-law of Shoshenq I, founder of

the next (22nd) Dynasty. Therefore, according to Kitchen,

this rules out any overlap between the 21st and 22nd

Dynasties, as we proposed.

We responded in a letter (James & Morkot 1991), towards the end of which we focussed on his

"single example". We agreed it is known that a 21st-dynasty Pharaoh called Psusennes was the contemporary of

Shoshenq I. (Kitchen opted to call him his "brother-in-law".) This in itself shows that there was some overlap

between the two dynasties. Further, there is no evidence

that this Psusennes was the successor of Siamun and hence

the last ruler of the 21st Dynasty, and thus nothing to

rule out our proposed overlap between the two dynasties.

We concluded that we "were confident that he [Kitchen]

cannot demonstrate their successive nature without

recourse to circular argument or reliance on Manetho [a

late source from Hellenistic Egypt]."

In his response Kitchen (1991b) failed to take up our

challenge. So, in a final rejoinder (James 1991) we noted:

Kenneth Kitchen appears to have conceded the major

point of his initial review. In our reply we

challenged Professor Kitchen to produce hard evidence

that the 21st and 22nd Egyptian Dynasties were

successive rather than overlapping. Since he failed to

respond, we can only assume he was unable to do so,

replying on different matters entirely.

To this date Kitchen has not replied to back up his

"single point" with any evidence, although he has never

lost opportunities to make critical remarks about our

work. His latest strategy has been limited to confusing

CoD with the secondary, and manifestly incorrect, efforts

of another author.

Kitchen also claimed that his case regarding the

relationship between dynasties 21 and 22 was "backed by

other evidence (the Neseramun family tree, etc)". What

the Neseramun genealogy says is actually rather

surprising. The family trees of Egyptian officials often

mention under which Pharaoh a given individual held

office. In this case the Neseramun genealogy specifically

states that Siamun was the contemporary of two

individuals. If Kitchen is right, one would expect from

the rest of the genealogy that these individuals lived

before the end of the 21st Dynasty. As it happens they

did not. In genealogical terms they lived one to two

generations after Shoshenq I, founder of the 22nd Dynasty.

At a conference on Mediterranean chronology in 1995 we

presented the evidence from the Neseramun and other

genealogies that Siamun must have been a contemporary of

the early 21st Dynasty (James et al. 1998, 32-4). The

evidence from the Neseramun family tree thus shows

completely the opposite of what Kitchen claimed.

Our point about the overlap between the 21st and 22nd

dynasties, which allows a lowering of Egyptian chronology,

has not completely fallen on deaf ears. Egyptologist

Aidan Dodson (1992) has conceded a possible 50-year

reduction, involving a small overlap between the

dynasties in question. In response to CoD, John Ray of

Cambridge (1992) also considered that a reduction of this

order is possible. Graham Hagens (1996) took up our

suggestion of a major overlap between dynasties in the

Journal for the American Research Center in Egypt.

Kitchen believes the 21st Dynasty ruled as an independent

entity for 125 years. We would propose reducing that

figure by a century, Hagens by 75 years. Kitchen's

attempt to debunk our restructuring of chronology should

now be a matter of increasing embarrassment.

Q6: Egyptologists say that they can retrocalculate, by

means of 'dead reckoning', from securely dated later

dynasties back through the Third Intermediate Period to

the New Kingdom. Is this true?

This claim is frequently made but is false. The lynchpin

for the Third Intermediate Period in Egypt is the

identification of Shoshenq I (founder of the 22nd Dynasty)

with a character mentioned in the Old Testament.

According to the First Book of Kings "Shishak king of

Egypt" invaded Judah in the fifth year of Rehoboam (c. 925

BC). Since Champollion's time it has been assumed that

Shoshenq I, who campaigned in Palestine in his Year 21,

was the same person as Shishak. This meant that

Egyptologists could use biblical chronology to date the

beginning of Shoshenq's reign, and hence that of the 22nd

Dynasty, to 945 BC. Various reign-lengths were then

assigned to fill up the time between this point and the

firmly fixed dates at the end of the TIP about 670 BC.

Yet Kitchen claims that he arrived at a 945 date for

Shoshenq I by 'dead reckoning', i.e. by adding up the

reigns of the pharaohs involved back from the 7th century

BC. This he manifestly did not do. To take just one

example, Pharaoh Takeloth I, who left no dated monuments

or documents at all, is given 14 or 15 years by Kitchen,

simply because of the need to fill the gulf of time

created by the Shoshenq=Shishak equation.

We are not alone in drawing attention to the fact that

egyptologists have been dishonest on this point.

Independently, Jeremy Hughes (1990, 190), an Oxford expert

on biblical chronology, has stated clearly:

Egyptian chronologists, without always admitting it,

have commonly based their chronology of this period on

the Biblical synchronism for Shoshenq's invasion.

The true situation was described with equal force by a

Harvard authority on biblical chronology, William Barnes

(1991, 66-7):

Although the present scholarly consensus seems to favor

a date c. 945 B.C.E. for the accession of Shishak ...,

apart from the biblical synchronism with Rehoboam

(which as I have noted above remains problematic at

best) there is no other external synchronism by which

one might date his reign, and the Egyptian

chronological data themselves remain too fragmentary to

permit chronological precision.

Egyptian chronology from the end of the New Kingdom

down to c. 670 BC is actually dependent on a single,

alleged synchronism with biblical chronology - and not on

supposed 'dead reckoning'.

Q7: But how can you dispute the obvious similarity between

the names Shoshenq and Shishak?

From a philological point of view Shoshenq and Shishak

make a good match, but there we feel the resemblance ends.

(As a caveat to the dangers of playing the 'name game' in

ancient history one can cite numerous spurious efforts,

though one example will suffice: in the 1940s someone

argued that the 'Derbe' and 'Lystra' visited by Paul the

Apostle - in Lycaonia in cental Asia Minor - were actually

located at 'Derby' and 'Leicester' in England. A good

phonetic match, but slightly implausible on other

grounds!)

Apart from the fact that both individuals were Pharaohs

who campaigned in Palestine, there is absolutely no match

between the accounts given of Shoshenq I and Shishak in

the respective Egyptian and biblical records. According

to the Old Testament, the focal point of Shishak's

campaign was the city of Jerusalem, before which he seized

fifteen Judahite cities fortified by Solomon's successor

Rehoboam. Only one of these towns, Aijalon, occurs in the

list of Palestinian place-names left by Shoshenq I at

Karnak. As Yohanan Aharoni (1966, 285) wrote in his

classic work on biblical geography:

It is clear from the Egyptian text that the main

objectives of the expedition were not the towns of

Judah and Jerusalem, but rather the kingdom of Israel

on the one hand and the Negeb of Judah on the other.

The situation may actually be worse than Aharoni

thought. Frank Clancey (1999) has recently argued that

Shoshenq's campaign was restricted to the Sinai, Negev,

southern hill country and Shephelah of Judah; though some

of his conclusions may be questioned, he has reinforced

the point that there is no evidence that the central hill

country around Jerusalem was involved. Admittedly, we do

not yet fully understand the purpose of the place-name

lists of foreign lands drawn up by the Pharaohs - they may

be towns conquered, neutralised or simply those they

passed through or received tribute from; nor can we demand

that the scribes who prepared Shoshenq's records had the

same perspective or concerns as those who prepared the

Hebrew account of Shishak's invasion. But the fact

remains that no case can be made for identifying the two

individuals from the geopolitics of their campaigns.

The superficial resemblance between the names Shoshenq

and Shishak may be just that. More importantly, the other

side of the coin is that acceptance of the equation has

done away with an identical name-match in Phoenician

history. Incriptions from Byblos reveal the following

sequence of kings:

Abibaal -------- contemporary Shoshenq I

Elibaal -------- contemporary Osorkon I (son of Shoshenq

I)

Shipitbaal (son of Elibaal)

The synchronisms with the 22nd-dynasty rulers Shoshenq and

Osorkon are known from the fact that in each case the

Byblite ruler had added his own inscription around the

cartouche of the Pharaoh, on statues imported from Egypt.

Following the conventional Egyptian chronology the Byblite

inscriptions have been dated to the 10th century. This,

however, has always caused problems. Many scholars have

preferred a later date, on palaeographic grounds, and the

late Benjamin Mazar was tempted to lower the date for the

whole series, making the last ruler Shipitbaal the same as

the "King Shipitbaal of Byblos" known from Assyrian

records around 740 BC. Mazar offered the suggestion twice

but, with the utmost reluctance, had to concede that the

Egyptian evidence seemed to date Shipitbaal nearer 900 BC.

More recently a detailed paper by epigrapher Ronald

Wallenfels has raised the spectre of the same synchronism,

which the conventional chronology is forced to reject.

Wallenfels produced a mass of evidence for redating the

Byblite insciptions to the 9th-7th centuries, and even

toyed with the idea of challenging the conventional date

for Shoshenq I. On the CoD model the conundrum is

resolved. Shoshenq I was not the biblical Shishak of c.

925 BC. Rather he campaigned in Palestine c. 800 BC and

the same date should be given to his contemporary Abibaal.

Shipitbaal, two reigns later than Abibaal, would then

after all be the king mentioned in Assyrian records about

740 BC. This is one of the many 'natural' synchronisms

between Egypt and Western Asia which CoD is able to

restore to ancient history.

Q8: Is it true that the conventional chronology of Egypt

is supported and proved to be correct by its synchronisms

with the chronology of Mesopotamia?

No, it is not true. Numerous synchronisms have been drawn

between Egypt and Mesopotamia, but many of these are based

on unproved assumptions. Of those that are genuine,

closer examination reveals that in many cases Mesopotamian

chronology is actually dependent on Egyptian - and not the

other way around. For example it is clear (Brinkman 1976)

that the list of kings for the late Kassite period in

Babylonia, conventionally 14th-13th centuries BC, has been

heavily restored from Egyptian and Hittite evidence.

(Hittite dating is directly dependent on that of Egypt.)

Where there are genuine synchronisms based on independent

Mesopotamian evidence, the model outlined in CoD provides

as many links as the conventional chronology, so there can

be no preference here for one model or the other. For

example, the conventional chronology has a convenient

match in the 14th century BC between the Assuruballit I of

the Assyrian King List and a like-named ruler who wrote

two letters to Pharaoh Akhnaton. (On the CoD model, the

contemporary of Akhnaton would have to be an otherwise

unattested Assuruballit 'II', as suggested by the fact

that the fathers of the Assuruballits concerned are

different in each case.) On the other hand, for example,

the CoD model offers a new synchronism in the 10th century

BC, between the Ini-Teshub, Hittite King of Carchemish,

and the Ini-Teshub, King of Carchemish, known from

Assyrian records. (For another 'new' synchronism see Q 7

above.)

Mesopotamian chronology itself is in need of serious

re-examination and revision. There are 'dark age' gaps

and archaeological anomalies during the 12th-10th

centuries in Assyria, Babylonia and neighbouring Persia

(Elam). During this period documentary evidence becomes

extremely scarce, and chronology is largely dependent on

the statements made in a King List drawn up by the

Assyrians in later times (9th-8th centuries BC). Yet it

has been shown by many scholars that this King List was an

artificial construct, the aim of which was to provide a

continuous line of kings stretching back into the distant

past, masking unofficial rulers and rival dynasties. In

the Assyrian dark age there is contemporary evidence that

there was more than one dynasty ruling. As argued in CoD,

two parallel dynasties ruled during the 11th to 10th

centuries period, which reduces Assyrian chronology by

some 110 years.

Work is ongoing on whether Assyrian chronology can be

further reduced. Model building is difficult, as there is

little controlling evidence on the data provided by the

Assyrian King List. Careful study of the fragmentary

eponym-lists (annual officials) could provide ways of

moderating the figures it gives.

Q9: How valid is the statement that CoD makes nonsense of

Biblical history by placing King David in the middle of

the reign of Ramesses II?

The statement is completely invalid, as CoD does not place

David in the middle of Ramesses' reign. The idea

originated with Kitchen (1991c, 238):

On their dates, King David would have carved out his

empire in Syria from the Euphrates to SW Palestine

right in the middle of the reigns of Ramesses II of

Egypt and the Hittite King Hattusil III, after their

peace-treaty ending two decades of war over who should

have how much of Syria. Is it even remotely

conceivable that these two formidable rulers should

just sit idly by, cowering with armies in mothballs,

while some upstart prince from Jerusalem's hills calmly

carved out three-quarters of their hotly-disputed

territories (and revenues) for himself? This is sheer

fantasy...

The chronology here is Kitchen's assumption, not ours.

The dates for King David are dependent on those for his

successor King Solomon. Ancient historians agree that the

reign of Solomon ended c. 930 BC, but hardly any (except

uncritical fundamentalists and Kitchen) accept the

schematic biblical figure of 40 years apiece for the

reigns of Solomon and David. Forty years for both reigns

together would be more realistic. This - on our

chronology - would place the unification of Israel under

Saul and David during the last years of Ramesses II and

the reign of his successor Merenptah. It is generally

acknowledged that the armies of Egypt were indeed sitting

idle during the last years of Ramesses II, while

Merenptah, though he campaigned in southern Palestine,

ruled a much reduced territory. Ramesses III later

described this time as the "empty years" when there was

chaos in the Egyptian empire.

We should also remember that the heartland of Israel

was the hill country in the interior, in which the

Egyptians showed no great interest. Their imperial

ambitions in Palestine were largely restricted to

controlling the rich cities of the coastal area and the

Jezreel Valley. Through most of the Late Bronze Age the

hill country was something of a backwater unaffected by

the Egyptian comings and goings through the more

economically important parts of Canaan. It is significant

that the first (and only) reference to Israel in Egyptian

records occurs in a stela of Merenptah which celebrates

the troubles afflicting neighbouring countries. One

enigmatic line, which has exercised scholarly imagination

for decades, states that "Israel is laid waste, his seed

is not". It is generally thought to mean that Merenptah

claimed to have bested Israel in a military conflict. But

a more literal translation might be safer, with the "seed"

referring to grain. As it was a standard Egyptian tactic

to destroy the fields and trees of enemies and rebels, it

seems that Merenptah was boasting about his raids on

Israelite fields. In the CoD chronology, the famine said

to have occurred during the reign of David (2 Samuel 21:1)

may reflect these circumstances.

In the same text Merenptah states that he conquered the

Canaanite city of Gezer, a fact which can provide us with

an invaluable synchronism. According to the Bible an

unnamed Egyptian Pharaoh became the father-in-law of

Solomon. As a dowry Solomon received the city of Gezer,

which this Pharaoh had recently conquered (1 Kings 9:16).

In the CoD model he must be Merenptah, who presumably

effected a rapprochement with Israel sometime after his

raids. During the reign of Solomon Egypt was clearly

friendly towards Israel, a policy which was reversed again

after Solomon's death.

Q10: If the Philistines arrived in Canaan in the time of

Ramesses III, whom CoD makes a contemporary of King

Solomon, how could they have fought his predecessors Saul

and David as mentioned in the Old Testament?

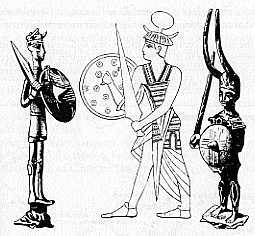

(Centre) A warrior of the Shardana, one of the

mysterious 'Sea Peoples', as depicted on Egyptian reliefs

conventionally dated to the 13th and 12th centuries BC.

Egyptian references to the Shardana continue until the

early 11th century BC. (Right and left) Bronze figurines

from Sardinia, usually dated to the 9th-7th centuries BC.

While it is tempting to draw some connection between the

two groups they are presently separated by over two

centuries.

|

|

Quite simply we dispute the idea that the Philistines

first appeared in Canaan during the reign of Ramesses III.

The interpretation of that Pharaoh's records regarding the

so-called Sea Peoples (including the Plst who are

generally thought to be the Philistines) has been the

subject of increasing debate over recent years. How much

these records describe the arrival of peoples or tribes

new to the Levant is a moot point, but some aspects of the

problem have been clarified. When the Philistines (Plst)

and their confederates transgressed the "borders" of Egypt

in the years 5 and 8 of Ramesses III, his scribes always

referred to them using the traditional terms for

"Asiatics" (a geographical rather than ethnic term).

Moreover, Ramesses III's inscriptions specifically mention

the towns and orchards of the Plst - which stands clearly

against the idea that they were all new arrivals from

elsewhere in the Mediterranean. Many Plst must have

already been settled in southern Palestine. These points,

originally stressed by Alessandra Nibbi (1975), have since

been echoed in the work of other scholars including Peter

James (in numerous lectures and in an unfinished

postgraduate thesis of the early 1980s), Phoenician

archaeologist Patricia Bikai (1992) and classicist Bob

Drews (1993, 52-3).

The Philistine problem is extremely complex but, in

short, there is a growing school of thought which regards

the so-called 'Sea Peoples' invasion as having been

overstated. This, while it does not rule out new

settlements of peoples from Cyprus and the Aegean at the

transition from the Late Bronze to Iron Ages, does stress

that the Plst were already an entity in coastal Palestine

before the reign of Ramesses III. On the archaeological

side, while the Philistines adopted the latest Aegean-style pottery at the beginning of the Iron Age (Monochrome

'Philistine Ware'), this cannot be taken as proof that

they had only just arrived; it may only reflect new

settlers that had joined them. In our archaeological

model Philistine presence during the Late Bronze Age is

reflected by, among other things, the 'Bichrome Painted'

pottery (thought to be Cypriot in origin) of the coastal

region. The 'foreignness' of the Philistines, as

perceived by the Hebrews, who always distinguished them

from the Canaanites, springs from their long-standing

relationship with Cyprus and the Aegean - a relationship

that continued in the Iron Age but had its origins much

earlier.

There is, therefore, no conflict between the idea that

Saul and David fought the Philistines before the reign of

Ramesses III, since Philistines were already present in

Palestine. Incidentally, this would also mean that at

least some of the biblical references to Philistines in

earlier times - e.g. those at the time of the Israelite

Conquest/Settlement - need not be 'anachronistic', as the

conventional chronology assumes them to be.

Q 11: Have any valid criticisms been levelled at CoD which

the authors have not been able to answer?

No, not yet. We are still waiting to be proved wrong, and

should this ever happen we would readily accept it. But

we insist that CoD can only be disproved by good evidence

and argument, not fudge and misinterpretation.

Q12: Is there any truth in the rumour that scholars have

fabricated or falsified evidence in order to disprove CoD?

Unfortunately, yes. Reactions to our theory have

exhibited examples of the most dubious side of

scholarship, ranging from the time-honoured practice of

misciting one's opponents, through sheer misstatements of

fact, to actual fabrication. Here are a few examples:

In a 'critique' of CoD Egyptologist Professor Frank

Yurco (1993, 10) claimed that we had overlooked "an

important synchronism". He stated that at the battle of

Karkar (Syria) in 853 BC, Pharaoh Osorkon II of Egypt

contributed 1,000 troops to fight king Shalmaneser III of

Assyria. If that were the case, our redating of Osorkon

II to the 8th century would be impossible. However, Yurco

seems to be unaware of what a synchronism means. A

synchronism between two individuals requires that two

names are given. The Assyrian texts of Shalmaneser III do

indeed refer to an Egyptian contingent at the battle of

Karkar. But they do not name the Pharaoh who sent them.

Yurco has simply supplied that name, probably by reference

to the chronological tables in Kitchen's book. In this

circular argument, and all other respects, Yurco's

'critique' was so shoddily researched that it would shame

an undergraduate.

We stated that Ramesses III (of the 20th Dynasty) used

the abbreviation of his name 'Sesi'. This concerns an

important point, as on our model we have suggested that he

is to be identified with the Egyptian king 'Shishak' who

invaded Palestine c. 925 BC. (The Hebrew text was

originally unpointed, so that strictly speaking the name

should be read as 'Shyshk' or 'Sysk'.) Kitchen (1991c,

236), with amazing effrontery, denied that Ramesses III

used the abbreviated form of his name. Effrontery is the

only word one can use, because Kitchen himself had

published the evidence to show that Ramesses III used the

name Sesi on an inscription from Medinet Habu (see James

et al. 1992, 127). Unaware of Kitchen's convenient lapse

of memory, Yurco (1993, 11) simply repeated the claim.

Both have manipulated the facts to suit their

preconceptions.

The worst case, evidently one of sheer fabrication, appeared in a review of CoD by James Mellaart (1991/2), a

famous archaeologist and, until recently, a lecturer at

University College London. While he made some favourable

comments, he claimed to have access to an unpublished

cuneiform text which gives a list of synchronisms between

Lydia (a kingdom in western Turkey in classical times) and

Assyria, running back 21 generations from the 7th century

BC through to the Late Bronze Age. According to Mellaart

it confirmed the conventional chronology and made "short

shrift" of our model. Apparently some scholars were taken

in and rejoiced at our defeat. Alan Millard of Liverpool

University, a noted expert on Near Eastern languages,

praised Mellaart's review as "appropriately negative"

(1994, 27).

Quite incredibly, Mellaart has never produced any

evidence that such a unique text exists, outside his

imagination. Despite his best efforts, Professor David

Lewis, an eminent epigraphist at Oxford, could find no

trace of such a tablet. Other scholars, such as cuneiform

expert Professor David Hawkins of the School of Oriental

and African Studies, are confident that the text is simply

not real. With evident embarassment, the editor of the

Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society, which

had carried Mellaart's review, published a note, alongside

letters from ourselves (James & Kokkinos 1992/3) and Lewis, stating that Mellaart's "alleged

documents... should not be cited as valid source

material." (Gibson 1992/3, 82). And there this

extraordinary episode ended. Mellaart does not appear to

have mentioned his tablet since.

Q13: Have any of the conclusions in CoD been accepted by

other archaeologists and ancient historians?

Many of the individual conclusions arrived at in CoD (and

its pilot project Studies in Ancient Chronology 1,

published in 1987) have been accepted or subsequently

proposed by other scholars. Examples include:

We suggested that the 'Pantalica III (South)' phase in

Sicilian archaeology was a chronological phantom, and that

it should be completely scrapped. It used to occupy some

120 years between the end of the Cassibile phase (c. 850

BC) and the beginning of Greek colonisation in c. 735 BC,

creating a strange gap betweeen burnt native settlements

and the Greek colonies founded on top of them.

(Especially strange as we know that the Greeks drove out

the natives and burnt their settlements.) Our argument

has been accepted and augmented by Robin Leighton (1993),

a leading authority on the archaeology of Sicily.

Following us, he lowered the end of Cassibile down from

c. 850 BC to c. 735 BC.

We demonstrated that the Greek pottery finds from Tell

Abu Hawam on the coast of Israel cannot be used to prop up

the presently accepted high chronology for the Greek Iron

Age. This conclusion (with reference to our work) was

accepted in the handbook on Aegean chronology written by

Professor Peter Warren and Vronwy Hankey (1989, 167).

Mention of Tell Abu Hawam as a useful benchmark for Greek

Iron Age Greek chronology has now dropped out of the

literature.

We stressed that the classical traditions do not

consistently point to a date for the Trojan War in the

12th century BC or earlier but, particularly using

genealogical material, that dates can be calculated as

late as the tenth century BC. Walter Burkert (1995) has

since reached the same conclusions.

We pointed out that the astronomical information on

the Ammizaduga Tablets, generally used to date the fall of

the First Dynasty of Babylon to 1595 BC, "provide no

serious obstacle" to a substantial lowering of

Mesopotamian chronology. In fact we noted that the

tablets would allow the Hittite sack of Babylon to "have

taken place in 1466 BC". Recently H. Gasche et al. (1998)

have argued for redating Babylon's fall to 1499 BC, a

century later than the conventionally preferred date.

Following our criticisms of Sothic dating, most

Egyptologists have now abandoned reliance on this method

(see Q1 above).

We have argued that the chronology of the early 25th

(Nubian) dynasty in Egypt needs shortening - specifically

we have lowered the beginning of the reign of Shabaqo in

Egypt to c. 708/707 BC. Subsequently a date of 706 BC was argued by Egyptologist L. Depuydt (1993), though with no reference to our work.

We suggested that the reigns of the 22nd Dynasty

pharaohs Shoshenq III and Takeloth II overlapped by some

20 years. This was argued independently by Egyptologist

David Aston (1989).

We argued that there was a considerable overlap

between the 21st and 22nd Egyptian Dynasties. This has

been followed by Hagens (see Q5 above).

We claimed that the Iron I period in Palestine needs

to be drastically reduced. Again Hagens (1999) has

followed this, in a paper in Antiquity, Britain's leading

archaeological journal.

We put forward the idea that the Iron II (so-called

'Solomonic') period in Palestine should be lowered in date

from the 10th to the 9th century BC. As the evidence for

this is so strong, we predicted that within a few years

such a revision would be followed, but with disastrous

consequences. We feared that if done as a half-measure,

it would only succeed in creating a 'dark age' in

Palestine during the time of David and Solomon - it would,

nevertheless, be consistent with the dark periods

elsewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean. We jokingly

referred to this as the 'Thatcherite' solution to

chronology - "things have to get worse before they get

better". Our prediction has now been fulfilled by the

work of Israel Finkelstein (e.g. 1996), a leading Israeli

archaeologist, who has argued our 10th to 9th century

revision (without reference).

While the arguments in CoD are frequently being

borrowed by other scholars in a piecemeal fashion, there

is still reluctance to adopt - or sometimes even consider

- the scheme as a whole. The consequences are misleading,

as the case of Finkelstein illustrates. His lowering of

Iron Age chronology (while leaving the end of the Late

Bronze at its conventional placement) has created the

predicted 'dark age' for Israel in the 10th century BC

(see James & Kokkinos forthcoming). This caused an

unprecedented furore, as Finkelstein has stranded King

Solomon in an archaeological vacuum - against Old

Testament tradition. Not unexpectedly, his conclusion has

been eagerly seized by the rising school of 'minimalists'

within biblical scholarship - who are attempting to scotch

the historicity of the Bible, claiming that Saul, David,

Solomon and the early kings of Israel are merely

fictitious characters.

For the key site of Samaria, we proposed that levels

V-VI should not be seen as the last Israelite phase before

the Assyrian conquest of 722 BC, but as the final Assyrian

levels - with a terminal date no earlier than about 630

BC. Such a date has since been forcefully argued in a

doctoral thesis by the late Stig Forsberg (1995, 24).

Q14: Why has CoD not been generally accepted as the

correct chronology for the ancient world?

Archaeologists are usually specialists working in separate

fields. While they are happy to draw conclusions in their

own areas of study, they are reluctant to make assessments

of the problems in other areas. Because the issues raised

by CoD involve interconnections between all fields of

ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern studies, the

overall case is simply too difficult for most to

comprehend. As in any scientific discipline it is easier

to keep to the status quo and avoid 'sticking one's neck

out', as it were. Academic inertia, scholarly egotism, the

desire for promotion, teaching convenience and a number of

other reasons continually reinforce this attitude.

It is quite clear, for example, that no-one would be

encouraged to publish articles agreeing with our model -

they would probably be automatically rejected. We have

naturally encountered this problem ourselves. With

respect to academic journals, we have been frustrated by a

'lack of airtime' in which we could defend our case

against critics. For example, when the Cambridge

Archaeological Journal published lengthy, and sometimes

rambling and unjustified, criticisms from several

scholars, the editor declined to publish our reply in the

same issue and allowed only limited space in the next.

In the case of Antiquity, our reply to Manning and

Weninger's ill-considered treatment of the radiocarbon

evidence from the Aegean, was flatly rejected.

Despite such difficulties, and in the meantime, CoD has

become a respectable and widely known antidote to the

conventional chronology which is regularly cited in the

literature and used in numerous university courses.

Q15: Is there a single test that can be done to prove or

disprove CoD?

Unfortunately there is no deus ex machina. The problems

of ancient chronology we have highlighted are so vast and

complicated that there is no easy way to prove or disprove

CoD - i.e. to the satisfaction of all concerned. Only a

combination of tests, including more rigorous studies of

comparative typology and stratigraphy, hand-in-hand with

scientific dating methods, will ultimately provide the

answer.

Having said that, and as most archaeologists accept the

primacy of radiocarbon dating, an extensive series of

fresh C14 results should by itself go a long way to

resolving whether we are right in lowering the end of the

Bronze Age by as much as 250 years. But, to achieve this

kind of chronological 'fine tuning' - though revolutionary

in archaeological terms - far more than the usual handful

of determinations would be needed. An adequate test of

CoD should involve a new suite of well-chosen samples,

short-lived and from secure contexts, each divided into

three parts and sent to as many laboratories. Radiocarbon

labs are normally informed of the expected archaeological

date of submitted material, but in this case 'blind

testing' should be followed. The samples must range

between a number of different sites, thus providing

further control. Were such a programme to be undertaken,

we are confident that the results will clearly be

discrepant with the conventional chronology but in harmony

with that in CoD.

References

- Aharoni, Y., 1966. Land of the Bible (London: Burns &

Oates).

- Aston, D., 1989. "Takeloth II - A King of the 'Twenty-Third Dynasty'", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 75,

pp. 139-53.

- Barnes, W. M., 1991. Studies in the Chronology of the

Divided Monarchy of Israel (Atlanta, Ga: Scholars

Press).

- Bikai, P. M., 1992. "The Phoenicians", in W. A. Ward & M.

S. Joukowsky (eds), The Crisis Years: The 12th Century

B.C.: From Beyond the Danube to the Tigris (Dubuque,

IA: Kendall/Hunt), pp. 132-41.

- Brinkman, J. A., 1976. Materials and Studies for Kassite

History (Chicago: Oriental Institute).

- Brown, A., 1991. "News from the Time Bandits", The

Independent on Sunday, 17 November, pp. 14-15.

- Burkert, W., 1995. "Lydia Between East and West or How to

Date the Trojan War: A Study in Herodotus", in J. B.

Carter & S. P. Morris (eds), The Ages of Homer: A

Tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule (Austin, TX:

University of Texas Press), pp. 139-48.

- Clancey, F., 1999. "Shishak/Shoshenq's Travels", Journal

for the Study of the Old Testament 86, pp. 3-23.

- Depuydt, L., 1993. "The Date of Piye's Egyptian Campaign

and the Chronology of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty",

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79, pp. 269-74.

- Dodson, A., 1992. Review of 'Centuries of Darkness',

Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 124, pp. 71-72.

- Drews, R., 1993. The End of the Bronze Age (Princeton

University Press).

- Finkelstein, I., 1996. "The Archaeology of the United

Monarchy: An Alternative View", Levant 28, pp. 177-87.

- Forsberg, S., 1995. Near Eastern Destruction Datings as

Sources for Greek and Near Eastern Iron Age Chronology.

Archaeological and Historical Studies. The Cases of

Samaria and Tarsus (696 B.C.) (Boreas 19 - Uppsala

University Press).

- Gasche, H., Armstrong, J. A., Cole, S. W. & Gurzadyan, V.

G. 1998. Dating the Fall of Babylon (Ghent/Chicago:

Mesopotamian History and Environment Memoirs).

- Gerding, H., 1997/8. Review of 'Centuries of Darkness',

Opuscula Atheniensia 22/23, pp. 157-60.

- Gibson, S., 1992/3. Editorial Comment, Bulletin of the

Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 12, p. 82.

- Hagens, G., 1996. "A Critical Review of Dead-Reckoning

from the 21st Dynasty", Journal of the American

Research Center in Egypt 33, pp. 153-63.

- Hagens, G., 1999. "An Ultra-Low Chronology of Iron Age

Palestine", Antiquity 73, pp. 431-39.

- Hankey, V. & Warren, P., 1989. Aegean Bronze Age

Chronology (Bristol Classical Press).

- Helck, W. 1989. Discussion. In P. Aström (ed.), High,

Middle or Low? Acts of an International Colloquium on

Absolute Chronology Held at the University of

Gothenburg 1987, Vol. 3 (Gothenburg: Paul Aströms

Förlag), pp. 40-43.

- Hughes, J., 1990. Secrets of the Times: Myth and History

in Biblical Chronology (Journal for the Study of the

Old Testament, Supplement Series 66 - Sheffield

Academic Press).

- James, P., 1991. Letter, reply to Kitchen, Times Literary Supplement, 12 July, p. 13.

- James, P. J. & Kokkinos, N., 1992/3. Letter, reply to Mellaart 1991/2, Bulletin of the

Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 12, p. 80.

- James, P & Kokkinos, N., forthcoming. "The Low Chronology

of the Tel Aviv School and its Ramifications".

- James, P. & Morkot, R., 1991. Letter, reply to Kitchen, Times Literary Supplement, 7 June, p.

15.

- James, P., Kokkinos, N., & Thorpe, I. J., 1998.

"Mediterranean Chronology in Crisis", in M. S. Balmuth

& R. H. Tykot (eds): Sardinian and Aegean Chronology:

Proceedings of the International Colloquium 'Sardinian

Stratigraphy and Mediterranean Chronology, Tufts

University, March 17-19, 1995 (Studies in Sardinian

Archaeology V - Oxford: Oxbow Books), pp. 29-43.

- James, P. J., Thorpe, I. J., Kokkinos, N., Frankish, J.,

1987. "Bronze to Iron Age Chronology in the Old World:

Time for a Reassessment?", Studies in Ancient

Chronology

1.

- James, P. J., Thorpe, I. J., Kokkinos, N., Morkot, R.,

Frankish, J., 1992. "Centuries of Darkness: A Reply to

Critics", Cambridge Archaeological Journal 2:1, pp.

127-30.

- Kitchen, K., 1991a. "Blind Dating" (Review of 'Centuries

of Darkness'), Times Literary Supplement, 17 May, p.

21.

- Kitchen, K. 1991b. Letter [reply to James & Morkot],

Times Literary Supplement, 26 June, p. 13.

- Kitchen, K., 1991c. "Egyptian Chronology: Problem or

Solution", Cambridge Archaeological Journal 1:2, pp.

235-39.

- Kuniholm, P. 1998. "Aegean Dendrochronology Project:

December 1998 Progress Report" Department of the History of Art, Cornell

University, Ithaca, N. Y. - circular).

- Leighton, R., 1993. "Sicily During the Centuries of

Darkness", Cambridge Archaeological Journal 3:2, pp.

271-76.

- Manning, S. W., 1990. "The Eruption of Thera: Date and

Implications", in D. A. Hardy & A. C., Renfrew (eds.),

Thera and the Aegean World III. Vol. 3: Chronology

(London: The Thera Foundation), pp. 29-40.

- Manning, S. W., 1992. "Thera, Sulphur and Climatic

Anomalies", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 11:3, pp.

245-53.

- Manning, S. W., 1998. "Correction. New GISP2 Ice-Core

Evidence Supports 17th Century BC Date for the

Santorini (Minoan) Eruption: Response to Zielinski &

Germani (1998)", Journal of Archaeological Science 25,

pp. 1039-42.

- Manning, S. W. & Weninger, B., 1992. "A Light in the

Dark: Archaeological Wiggle Matching and the Absolute

Chronology of the Close of the Aegean Late Bronze Age",

Antiquity 66, pp. 636-63.

- Mellaart, J., 1991/2. Review of 'Centuries of Darkness',

Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 11,

pp. 35-39.

- Millard, A.,1994. The Society for Old Testament Study, Book List, p. 27.

- Nibbi, A., 1975. The Sea Peoples and Egypt (Park Ridge,

N. J.: Noyes Press).

- Olsson, I. & El-Daousay, M. F. A. F., 1979. "Radiocarbon

Variations Determined by Egyptian Samples from Dra Abu

El-Naga", in R. Berger (ed.), Radiocarbon Dating:

Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference, Los

Angeles and La Jolla 1976 (Berkeley: University of

California Press), pp. 601-12.

- Ray, J., 1992. Review of 'Centuries of Darkness', Journal

of Hellenic Studies 112, pp. 213-14.

- Renfrew, C., 1996. "Kings, Tree-rings and the Old World",

Nature 381, pp. 733-34.

- Rose, L. 1994. "The Astronomical Evidence for Dating the

End of the Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt to the Early

Second Millennium: A Reassessment", Journal of Near

Eastern Studies 53, pp. 237-61.

- Snodgrass, A., 1991. "Collapses of Civilization" (Review

of 'Centuries of Darkness'), London Review of Books, 25

July 25, pp. 18-19.

- Yurco, F., 1993. "An Egyptological Response to 'Centuries

of Darkness'", in A. Leonard (ed.), Centuries of

Darkness: A Workshop Held at the 93rd Annual Meeting of

the Archaeological Institute of America, Chicago,

Illinois, USA, December 1991 (Colloquenda Mediterranea

A/2 - Bradford: Loid Publishing), pp. 8-13.

- Zielinski, G. A., et al., 1994. "Record of Volcanism

Since 7000 B.C. from the GISP2 Greenland Ice Core and

Implications for the Volcano-Climate System", Science

264 (13 May), pp. 948-52.

- Zielinski, G. A. & Germani, M. S., 1998a. "New Ice Core

Evidence Challenges a 1620s B.C. Age for the Santorini

(Minoan) Eruption", Journal of Archaeological Science

25, pp. 279-89.

- Zielinski, G. A. & Germani, M. S., 1998b. "Reply to:

Correction. New GISP2 Ice-Core Evidence Supports 17th

Century BC Date for the Santorini (Minoan) Eruption",

Journal of Archaeological Science 25, pp. 1043-45.

|